Contact Us

Subscribe to Causeway Insights, delivered to your inbox.

Value’s prolonged underperformance has tried investors’ patience and, for some, raised doubts about the viability of the investment style. As an active value manager, Causeway is no stranger to the frustrations of the style’s extended unpopularity. But we are more convinced than ever that a diligent, rigorous investment approach rooted in the fundamentals of value investing will ultimately prove fruitful. After such weak performance, we believe value stocks demonstrate more alpha-generation potential than ever before—and not simply because we believe in mean reversion. To explore the challenges posed to the investment style and argue our case for value investing, Will Tsui, Director of Consultant Relations, asks Ryan Myers, Senior Quantitative Research Analyst and Strategist, the tough questions about value investing and its recent performance.

WT: Ryan, let’s tackle the elephant in the room head-on: Is value investing dead?

RM: That depends on how you define value investing. If you’re talking about the passive approach of buying all cheap stocks based on simple metrics, then yes, value investing has been ineffective for years. The market has become far more efficient since Fama and French first discovered that stocks with high book-value-to-market-price multiples outperformed those with lower multiples.[1] But within active management, it is a completely different story. Cheap stocks typically trade at a discount to peers for a reason. The most important job of the value investor is to distinguish between companies that have temporarily “de-rated” from those that are structurally broken and will remain cheap until the day they cease operations. And thus, investigative analysis is more important than ever.

In the long run, even in a world with zero interest rates, the market simply cannot ignore realized cash flow and return of capital.

At Causeway, we do not buy stocks just because they appear cheap. For our fundamental portfolios, we identify and research stocks trading at significant discounts to what we perceive to be their intrinsic value. Value investing requires discipline and experience to assess a stock’s intrinsic value in multiple future states of the world and to avoid overpaying relative to fundamentals. In the long run, even in a world with zero interest rates, the market simply cannot ignore realized cash flow and return of capital. History has shown that maintaining a value discipline, particularly when value has been out of favor, has produced stronger relative returns and lower volatility than a growth orientation over full market cycles. Value stocks can take years to “re-rate” upward and, as with any consistent investing strategy, a value style will underperform the broader market from time to time. This is simply the price of being contrarian.

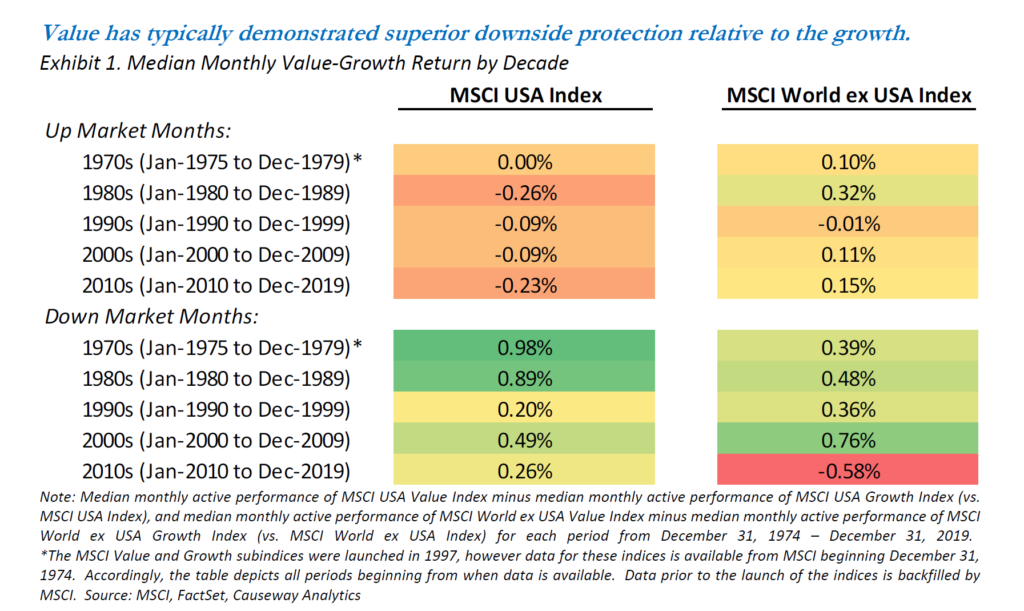

WT: People tend to associate the benefit of the value premium with downside protection. Is there evidence to support that?

RM: Value does have a history of outperforming in down markets. In Exhibit 1, you can see that the MSCI USA Value Index has outperformed the MSCI USA Growth Index in down markets across all decades, including the 2010s (but there were not that many down months in the last decade). Internationally, you will see that the MSCI World ex USA Value Index has generally outperformed the MSCI World ex USA Growth Index in up markets and down markets, reflecting value’s superior performance abroad.

However, relative downside protection should not be reason enough to invest in value strategies. Value is not a hedge to all forms of market risk; rather, it is a specific hedge to the risk of overpaying for assets. That risk is present in all market regimes.

WT: The historical relationship is there, except importantly in the past decade. Has something about value’s performance potential fundamentally changed? Might it continue to underperform in both up and down markets?

RM: It is easy to become discouraged by the length and depth of value’s underperformance. Since the Global Financial Crisis, however, there have been sporadic value rallies in 2009, 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2019. Those rallies have been abrupt and swift, which is how value rallies have tended to materialize. They are easy to miss if you switch exposure at the wrong time. But also remember that value can go through long periods of outperformance such as the mid-1990s or early 2000s.

Value has an important role as long as economic cycles exist and, despite heroic efforts, monetary and fiscal initiatives can only dampen them so much.

But yes, a decade can seem like a long time, particularly when we have just lived through it. Is that enough evidence to declare value dead? Value has an important role as long as economic cycles exist and, despite heroic efforts, monetary and fiscal initiatives can only dampen them so much. We believe value’s underperformance in the recent past is not due to a permanent deterioration of the value premium, but rather the result of the prevailing interest rate environment and behavioral biases that have temporarily disrupted the important process of price discovery for investors.

As we demonstrated in a research note last summer (“Rationalizing the Irrational”), recent growth outperformance is not due to superior earnings growth, but rather to the market’s revaluation of those earnings in the form of higher multiples. Falling interest rates have undoubtedly played a major role. Decreasing the discount rate applied to cash flows will necessarily increase their present value. Since growth stocks tend to have more of their cash flows expected in years far in the future (i.e., longer duration), falling interest rates will have a more positive impact on the present value of growth stocks relative to value stocks.

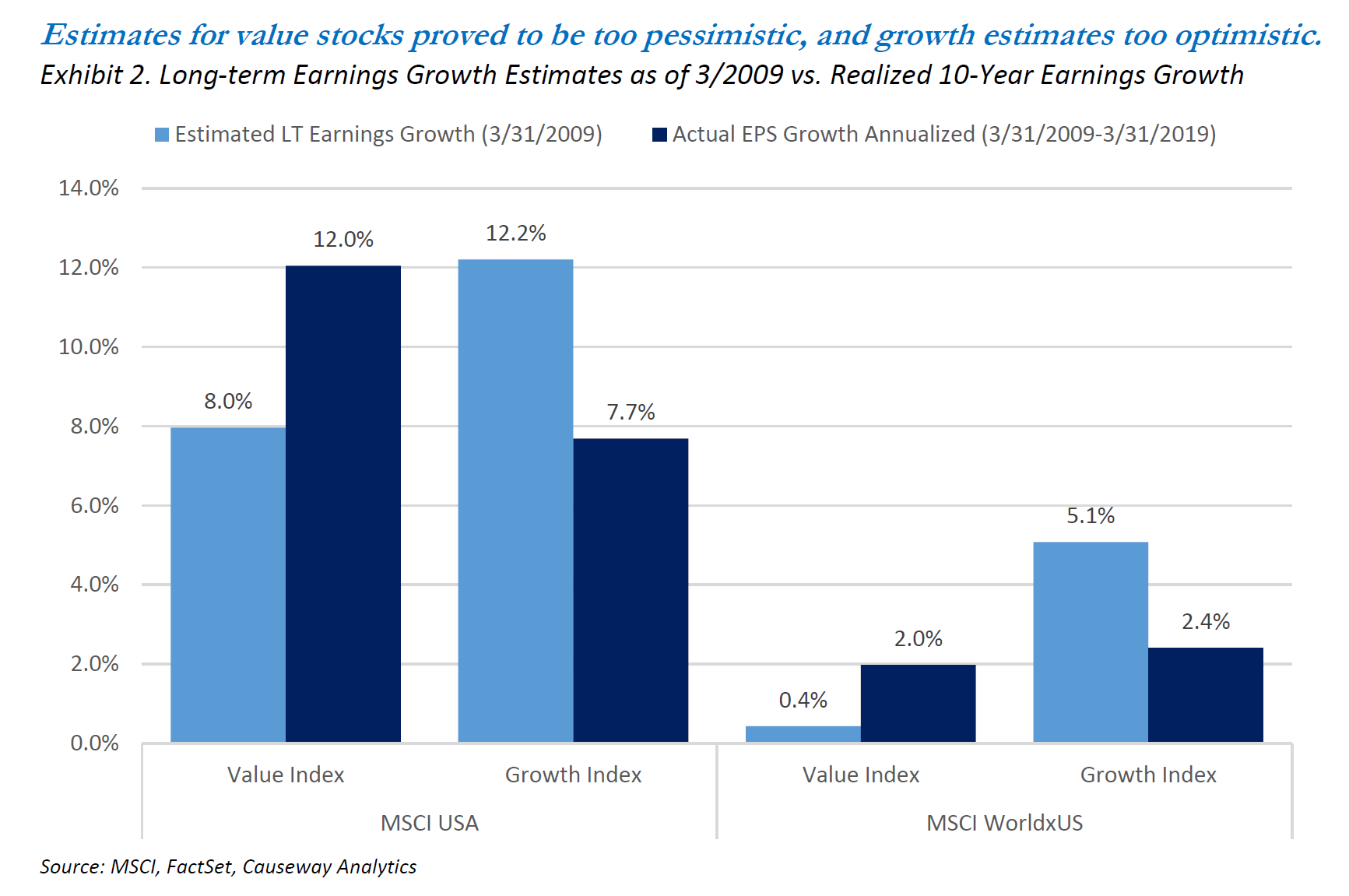

There also exists a behavioral bias to overestimate earnings growth rates for growth stocks and underestimate them for value stocks.

As evidence that this bias is real, let’s rewind to the market trough of the Global Financial Crisis in March 2009. Aggregating all sell-side estimates to the index level, analysts assumed earnings for the USA Value Index would grow by 8% annually in the foreseeable future, while earnings for the USA Growth Index would grow by 12% annually (the light blue bars in the chart below). Internationally, earnings growth expectations were lower across the board, but analysts still had much higher growth expectations for the MSCI World ex USA Growth Index.

Now let’s fast-forward ten years and see how fast realized (Last Twelve Months) earnings actually grew (dark blue bars). Earnings for the value indices grew faster than projected, and earnings for growth indices grew slower than expected. In the US, value earnings actually outgrew growth earnings.

We see these biases playing out again in the current environment. Analysts are ascribing much higher long-term growth (LTG) rates to growth stocks. As of March 31, 2020, the LTG rate was 14.8% and 7.0% for the MSCI USA Growth and Value Index earnings, respectively. Outside the US, the LTG rate was 9.2% and 5.3% for the MSCI World ex-US Growth and Value indices, respectively.

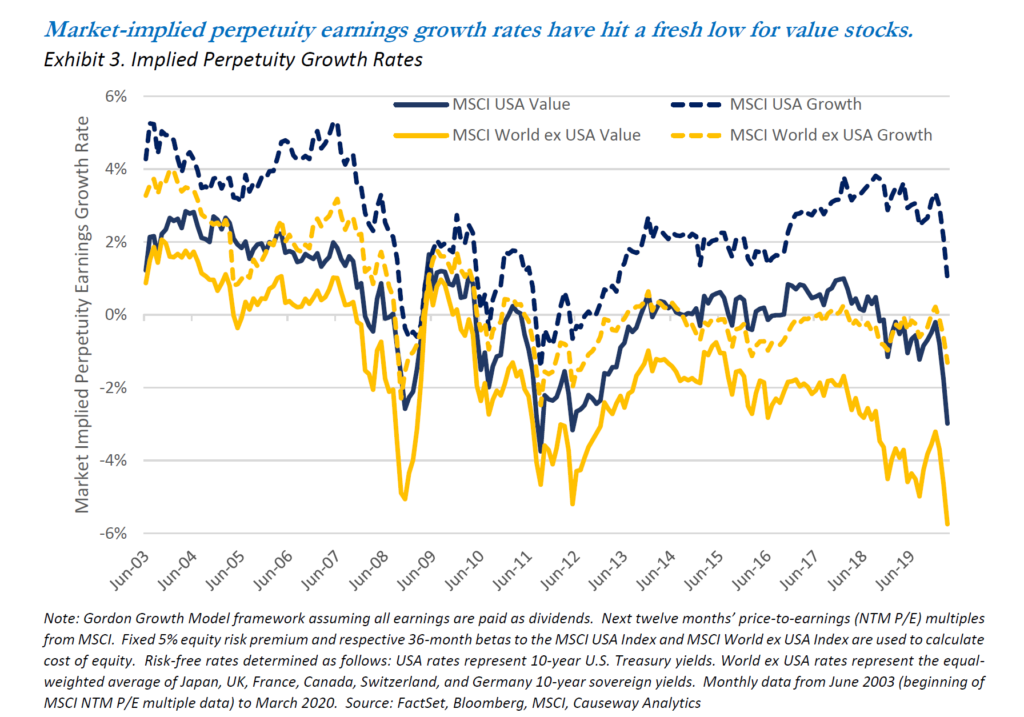

Alternatively, we can derive what the market itself assumes. We can use a model of intrinsic value known as the Gordon Growth Model to solve for the implied perpetuity growth rate using current index multiples. Exhibit 3 plots what current market multiples imply about assumed future perpetuity earnings growth rates.

In the chart above, the solid lines represent the implied perpetuity growth for the value indices and the dashed lines represent implied growth rates for the growth indices. At current multiples, the market is assuming significantly negative earnings growth in perpetuity for value indices in both regions. The implied earnings growth rate for the MSCI World ex USA Value Index is currently at a historical low. Negative 6% earnings growth annually—forever? That seems absurdly low. Yes, 2020 earnings growth will be significantly negative for most companies challenged by coronavirus, but gross domestic product (GDP) growth and corporate profits will eventually recover. Value stocks are currently pricing in a permanent depression that is seemingly incompatible with economic history.

WT: Focusing in on 2020 year-to-date performance, are there other reasons value has been so weak?

RM: If you’re referring to index performance, much of value’s underperformance in the 2020 coronavirus drawdown has come from sector biases in the MSCI Value and Growth indices. The value indices are significantly overweight energy and financials, the two worst-performing sectors (both in the US and internationally) in the 2020 February and March drawdown.

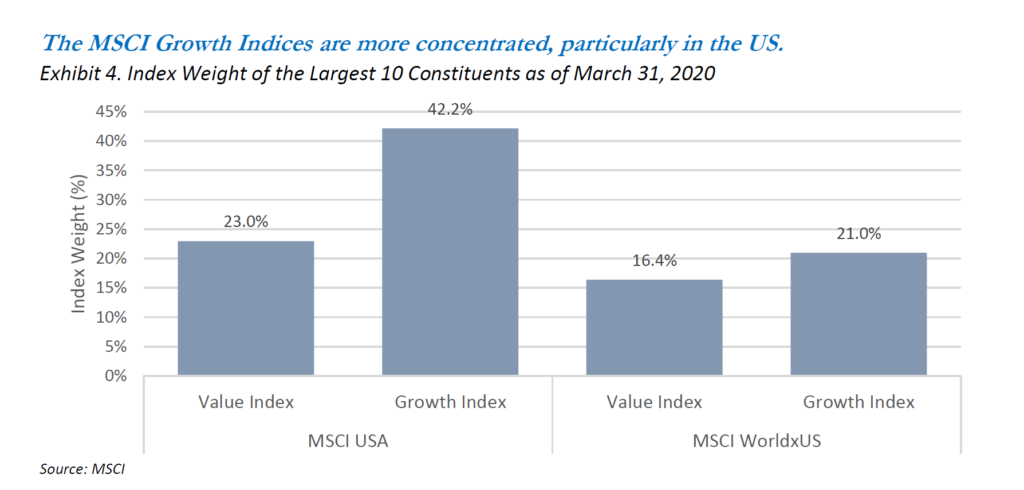

Meanwhile, leadership in the growth indices has been concentrated among the well-established, mega-cap growth stocks, and they can easily move the entire growth indices by virtue of their size. In the market’s attempt to adjust to our new reality, much industrial disruption is being priced in and certain technology-focused growth stocks should profit from expected structural shifts in a socially distanced world. The much higher concentration and narrower leadership of the growth indices (especially in the US) has boosted their returns in late-March/early-April, and partially eclipsed the recovery of the value indices in relative performance terms.

Growth and value are not mutually exclusive, especially right now. As value investors, we are not anti-growth; rather, we are disciplined in what we will pay for that growth.

WT: So, where do we go from here? If the interest rate regime is unlikely to change anytime soon, and style benchmark construction favors growth’s outperformance, what catalyst will prompt value’s return to favor?

RM: Although risk-free rates seem likely to stay at or near zero (or even negative in some countries) for an extended period, that does not mean investors are indifferent between cash flows today and those ten years in the future. Amid the COVID-19 market tumult, corporate credit spreads have jumped, costs of capital have increased in many cases, and investors are reassessing the price they are paying for a given earnings stream. Companies with rapid top-line growth but no profits have suddenly found capital increasingly more difficult to raise (as evidenced by recent plunges in valuations of WeWork and other cash-burning “unicorns”). And investors have already begun snapping up the historically low-multiple bargains created by the February and March sell-off.

Growth and value are not mutually exclusive, especially right now. As value investors, we are not anti-growth; rather, we are disciplined in what we will pay for that growth. The behavioral foundations of the value premium clearly exist in our view, creating opportunities for value investors. If projected earnings growth is nearly always biased, then the astute value investor can find bargains among those stocks that the market has mispriced.

In the current dislocation, we are finding value stocks with the best growth potential we have seen in years. They may not have the glamour of initial disruptors, but they do not have the high price tag either. Instead, they are under-the-radar market leaders trading at valuations that imply a permanent impairment of profitability from the weak global economy. Well-capitalized and typically scale players, these companies should find their competitive positions further strengthened by market consolidation. With a crisis to catalyze significant costs cuts, and divestment of low return assets, many of these companies are actively taking steps to improve their operating leverage. And with a recovery in revenue growth, their earnings should snap back from the lows of the economic cycle.

We view our role as champions of misunderstood stocks.

WT: You describe a value investor who cares about growth – how does Causeway fit within the traditional categories of value investing (e.g., Deep Value, Relative Value, Intrinsic Value)?

RM: We view our role as champions of misunderstood stocks. We find companies for our fundamental portfolios with experienced management teams able to implement operational restructuring to restart earnings growth. The most reliable way to outperform an index is to buy assets at substantial discounts to their intrinsic value, and that usually happens when investors fundamentally misunderstand a stock’s future prospects. Sometimes it takes years for a company to prove itself and achieve its intrinsic value—in those cases, we look for capital return to shareholders, such as dividend income, so that we are paid to wait. If a stock trades lower but fundamentals remain unchanged, the upside-to-downside ratio improves and the increasingly asymmetric return profile becomes more attractive. At Causeway, because our research gives us conviction in our price targets, we like to add to positions on these price declines. This focus on getting as low an entry price as possible defines the active value manager. We seek to buy when others are selling and sell as they buy. Although timing cannot be predicted, we believe eventually value works—the pendulum swings the other way, and cheap stocks ultimately outperform. We believe contrarian investors who can withstand value drawdowns are ultimately rewarded for their patience by the subsequent snap-back and re-rating.

WT: How can active value managers separate themselves from dependence on value’s mean reversion?

RM: Causeway’s International and Global Value Equity strategies are not inextricably linked to the value cycle because our portfolio candidates do not always conform to simple definitions of value. Causeway’s definition of value derives from our multi-year investment horizon. As part of our stock selection process, we thoroughly evaluate all aspects of the investment case, seeking to identify stocks trading at discounts to intrinsic value. We exercise conservatism and scenario testing in determining a stock’s value, and if the stock does not offer reasonable upside for the incremental risk (defined as standard deviation of returns) that it will contribute to the portfolio, it will not be added. In contrast, static, short-term definitions of value would miss stocks where value is not readily apparent. Those buy candidates may look expensive on current or next year multiples, but look compelling with a cyclical upturn and/or operational recovery. For the past several years, this was the case with several of our “self-help” portfolio constituents that were (and still are) undergoing multi-year transformations.

WT: What opportunities is Causeway’s approach uncovering in the current environment?

RM: We have found abundant opportunities in certain industries hardest hit by the coronavirus. Cyclical stocks have incurred the greatest selling pressure in this global stock market meltdown, and many are trading at valuations that suggest significant and permanent earnings impairment. Market fear of industrials, financials, and consumer discretionary stocks, among others, has presented us with a chance to give our clients access to an eventual recovery in industrial activity, bank margins and profitability, and consumer confidence and spending. We believe high-quality cyclicals will lead the market recovery as they have in the past.

This market dislocation has given us the rare opportunity to avoid making the typical tradeoffs between value, growth, and quality.

How do we assess quality? In the short term, it comes down to focusing on stocks with high liquidity and manageable leverage to “weather the storm.” Some cyclical companies will undoubtedly face credit and liquidity hurdles in the coming months. In the long-term, it means buying companies with strong competitive positions. We find Porter’s “Five Forces” model a useful framework here. We prefer companies in industries with low competition, high barriers to entry, minimal threats from substitutes, low supplier power, and minimal customer power over pricing.

This market dislocation has given us the rare opportunity to avoid making the typical tradeoffs between value, growth, and quality. We have added companies that we believe have strong management teams, defensible franchises, and high growth rates, all at bargain prices.

[1] In their 1992 Journal of Financial Studies article, “The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns,” Eugene Fama and Ken French are widely credited with first documenting the value premium (which they defined as the difference in returns between high book-value-to-market-price stocks and low book-value-to-market-price stocks) in the US during the period they studied (1963-1990).

This market commentary expresses Causeway’s views as of April 2020 and should not be relied on as research or investment advice regarding any stock. These views and any portfolio holdings and characteristics are subject to change. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. Forecasts are subject to numerous assumptions, risks and uncertainties, which change over time, and Causeway undertakes no duty to update any such forecasts. Information and data presented has been developed internally and/or obtained from sources believed to be reliable; however, Causeway does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy or completeness of such information.

International investing may involve risk of capital loss from unfavorable fluctuations in currency values, from differences in generally accepted accounting principles, or from economic or political instability in other nations.

The MSCI USA Index is a free float-adjusted market capitalization index, designed to measure the performance of the large and mid cap segments of the US market. The MSCI USA Value Index is a subset of the MSCI USA Index, and targets 50% coverage of the MSCI USA Index, with value investment style characteristics for index construction using three variables: book value to price, 12-month forward earnings to price, and dividend yield. The MSCI USA Growth Index is a subset of the MSCI USA Index, and targets the remaining 50% coverage.

The MSCI World ex USA Index is a free float-adjusted market capitalization index, designed to capture large and mid cap segments across 22 of 23 developed markets countries, excluding the United States. The MSCI World ex USA Value Index is a subset of the MSCI World ex USA Index, and targets 50% coverage of the MSCI World ex USA Index, with value investment style characteristics for index construction using three variables: book value to price, 12-month forward earnings to price, and dividend yield. The MSCI World ex USA Growth Index is a subset of the MSCI World ex USA Index, and targets the remaining 50% coverage.

These MSCI indices are gross of withholding taxes, assume reinvestment of dividends and capital gains, and assume no management, custody, transaction or other expenses. It is not possible to invest directly in an Index.

MSCI has not approved, reviewed or produced this report, makes no express or implied warranties or representations and is not liable whatsoever for any data in the report. You may not redistribute the MSCI data or use it as a basis for other indices or investment products.

“Gordon Growth Model” is used to determine the intrinsic value of a stock based on a future series of earnings (or dividends) that grow at a constant rate. Given an earnings per share (or dividend per share) that is payable in one year, and the assumption that the earnings (or dividends) grow at a constant rate in perpetuity, the model seeks to solve for the present value of the infinite series of future earnings (or dividends).