Contact Us

Subscribe to Causeway Insights, delivered to your inbox.

There is no easy way to reach India from Los Angeles. Transiting through Hong Kong, it takes a full 24 hours, several meals and almost 10,000 total flight miles to land in Mumbai. Despite the distance, Causeway’s fundamental analysts and portfolio managers have put this populous country on our radar. Unsurprisingly, India’s demographic bulge of young consumers reportedly wants to buy smart phones, cars and homes, and their spending power rises annually. India’s real gross domestic product (GDP) growth of 7.3% for 2016 tops the charts of major countries, including China. Political and economic advances—such as the country’s recent demonetization to encourage a shift from a cash to digital economy—should herald (taxable) growth. It seems likely that rising tax revenues will fund more essential infrastructure to facilitate economic expansion, creating a potential virtuous cycle for investors and lenders. We have invested in India’s stock market since 2007 in our quantitative emerging markets strategy. We believe we have been successful, and continually strive to improve upon those successes. As Causeway’s fundamental investment research extends its reach into all the major emerging markets, we expect our team-wide understanding of economies, sectors and companies to benefit both fundamental and quantitative research. Regarding this knowledge expansion, Causeway’s quantitative portfolio manager, Arjun Jayaraman, and senior research analyst, Victor Liu, compared thoughts on emerging markets and the opportunity in India.

Q: Arjun, what tools does Causeway quantitative research share with fundamental research to focus the team’s attention on the right countries and companies?

AJ: Every week, Causeway’s proprietary “Alpha Factor” screen sifts through stocks in the MSCI emerging markets universe for those with a free float at or above a threshold – currently $5 billion – then for specific bottom-up factors (such as valuation, earnings growth, price momentum) and macro-related and currency factors. Our analysts and portfolio managers prefer to visit regions rated highly by our quantitative macroeconomic country score, which is currently comprised of factors based on changes in real GDP, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development LEI (a composite of leading economic indicators), current accounts, industrial production, real interest rates, yield curves and credit default swap spreads. Over the past nine years (from inception of our emerging markets strategy), our quantitative factors typically have indicated markets and stocks with promise.

Q: What happens to the stocks that pass the emerging markets screen?

VL: Of this subset, we aim to meet with the larger companies at least once a year. In these meetings, we have a dual objective: to deepen our understanding of the country, stock market and constituent companies, and to open a line of communication with company management. We ask questions of management emphasizing profitability and returns on capital, corporate governance, and frequently ask questions on other shareholder and socially responsible practices. We then compare answers with the company’s track record relative to global peers. Of the emerging markets-focused research trips we made in 2016, each identified “world class” companies enjoying some of the most rapid growth relative to global peers in their respective industries.

We think the next few years could be an especially propitious time for companies listed in India, as policy changes may reduce endemic corruption.

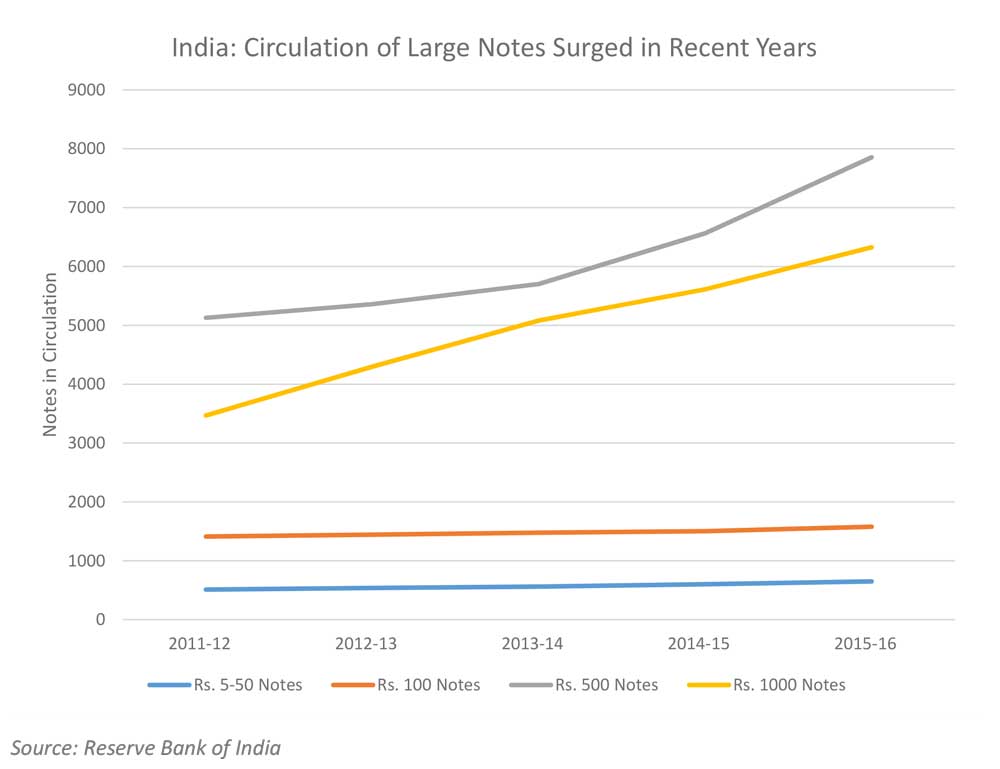

AJ: Clearly, not all of these rapidly growing companies currently trade at attractive valuations. And some regions appear considerably more interesting than others. We think the next few years could be an especially propitious time for companies listed in India, as policy changes may reduce endemic corruption. Until recently, almost 90% of transactions in India were in cash, a function of a large informal (unreported) segment of the economy. As of November 2016, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government made 86% of the roughly $240 billion of currency in circulation illegal by banning two banknote denominations. Residents of India had until the end of 2016 to exchange their cash, or it became worthless. A shortage of the legal tender placed severe working capital constraints on small businesses, as the banking system could not meet the demands of cash distribution. Longer term, we expect the formal, taxable economy to prosper. With another source of revenues, we believe the central and state governments should be able to fund much needed infrastructure projects. If Prime Minister Modi consolidates his power in 2017 state elections, the pace of economic reform may accelerate

The country’s demonetization has led to the opening of bank deposit accounts, offering India an opportunity to leapfrog several banking stages, avoiding checks and bank cards, and moving directly to digital payments.

VL: India’s cash economy creates payment inefficiencies, as low levels of bank savings result in higher costs of funds for India’s banks. The country’s demonetization has led to the opening of bank deposit accounts, offering India an opportunity to leapfrog several banking stages, avoiding checks and bank cards, and moving directly to digital payments. Non-cash transactions should increase rapidly, which we expect will lead to an increase in demand for point-of-sale technology, credit cards, and mobile banking—all strengths of the country’s private sector banks. An upstart mobile competitor we met with in India recognizes the potential for consumers to pay for data. The company’s senior management told us that of the over one billion mobile phone connections in India, approximately 85% are 2G cellular telecommunications networks and a mere 150 million mobile connections are 3G. Further, management noted that only approximately one third of India’s population has internet access, with only 30 million people accessing the internet from home with copper or fiber. Given the cost and regulatory delays of fiber on the ground, a massive expansion in mobile data usage seems inevitable. The arrival of 4G and smart phones should transform the country’s data consumption landscape.

Q: How do Causeway’s fundamental analysts share information from these research meetings with Causeway quantitative research?

VL: After an especially useful meeting, we send relevant information to all of our portfolio managers, both quantitative and fundamental. We typically request access to managements of the large capitalization companies. Those research meetings often shed light on an entire industry or market segment, enhancing our understanding of the smaller companies prevalent in our emerging markets strategy. For example, in Mumbai, we recently interviewed the chief financial officer of a large metals and mining company in our emerging markets portfolio. The CFO clarified the domestic supply/demand situation for its metals and smelting capacity utilization in India. In addition, we left that meeting better equipped to place a probability on the timing and magnitude of duties on specific metals imports, which would have an economic impact on industry players of all sizes.

From a quantitative perspective, we welcome this increasing flow of fundamental information about our emerging markets portfolio holdings, especially in areas such as changes in corporate governance, deteriorating financial strength, new competitors, and adverse regulations, to name just a few.

Q: What are the red flags that would concern you about an investment in India?

VL: Unfortunately, there are many. For India, we have scrutinized the promoter groups that solicit capital investments for companies, and their influence (for better or worse) on a company’s treatment of the other shareholders. Promoter groups tend to be large, sometimes dominant, shareholders. Theoretically, the promoters have similar goals as foreign institutional shareholders, although this is not always the case. A number of India’s largest companies are part of conglomerates. The conglomerate organization may create inefficiencies and conflicts of interest that impede the performance of an individual company. We remain watchful of the impact of these ownership structures on minority shareholders.

AJ: From a quantitative perspective, we welcome this increasing flow of fundamental information about our emerging markets portfolio holdings, especially in areas such as potentially negative changes in corporate governance (such as shareholder value destructive mergers and acquisitions), deteriorating financial strength, new competitors, and adverse regulations, to name just a few. We expect this convergence of quantitative and fundamental research to continue adding value for clients in each of our equity mandates.

Important Disclosures

This market commentary expresses Causeway’s views as of January 5, 2017 and should not be relied on as research or investment advice regarding any investment. These views and any portfolio holdings and characteristics are subject to change, and there is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. Any securities referenced do not represent all of the securities purchased, sold or recommended by Causeway. The reader should not assume that an investment in any securities referenced was or will be profitable. Forecasts are subject to numerous assumptions, risks and uncertainties, which change over time, and Causeway undertakes no duty to update any such forecasts. Information and data presented has been developed internally and/or obtained from sources believed to be reliable; however, Causeway does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy or completeness of such information.

MSCI has not approved, reviewed or produced this report, makes no express or implied warranties or representations and is not liable whatsoever for any data in the report. You may not redistribute the MSCI data or use it as a basis for other indices or investment products.